|

Use

of the Hip in Tang Soo Do

Master C. Terrigno

- 6th Dan

Editor - Tang Soo Do World

As

most Tang Soo Do practitioners know, the extensive

use of the hip is fundamental to our art and is its

most distinguishing feature - its "signature" which

sets us apart from other martial arts systems in

terms of how we move. At first glance, the correct

use of the hip may seem like a simple principle but

in reality it is a difficult one for both Gups and

Dans alike to internalize and execute properly.

Our late Great Grandmaster Hwang Kee devoted a

considerable amount of space in his textbook to the

"scientific use of the hip" in Tang Soo Do, so it is

imperative that practitioners take the time to fully

understand it and apply it early on in their

training so as not to create bad habits that will

later be difficult (and time consuming) to correct.

From personal experience I know the extra work it

takes to "un-learn" acquired muscle memory, although

my situation was not due to having formed bad habits

per se, but from having studied Japanese Karate for

six years prior to Tang Soo Do. Japanese karate

techniques are more linear and direct, with less hip

rotation compared to our art. Consequently, I had to

work extremely hard at overriding my instinctual

movements and replace them with the more circular

motions that Tang Soo Do is known for. I can still

hear my original Instructors, especially Master

Young Ki Hong admonishing me, always with the same

statement - Hu Ri, Hu Ri. And after a little while

he would just look me in the eye and with his ever

present smile simply say - more practice! Yes Sir, I

would respond. That was over 26 years ago, and I'm

still working at it.

The challenge for students with no prior training is

to overcome their natural tendency to use one part

or area of the body more than or in opposition to

the other(s). Men, because of their physical build

and strength are prone to predominately using the

upper body while at the same time applying too much

power, literally throwing themselves head first into

the movements.

To correct this, your Instructors have no doubt

urged you to "keep your back

straight", "move from your center or abdomen (Dan

Jun)", "rotate your hips (Hu Ri)", and

use "more trunk

twist". Easier said than done in many cases,

especially in the heat of training when there is no

time to stop and think, and maybe that is the point -

there is no time to think about a technique when

you're in the middle of it. The "thinking" should be

done when we're off the training floor. Consider it

the planning or research phase of your training.

|

|

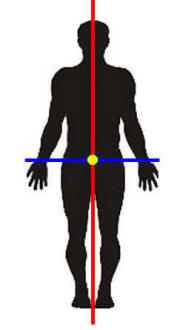

So to

help put these terms into visual context, consider the drawing at

right. The Hu Ri, or hip, is the blue horizontal line and the red

line is our central axis which keeps us in correct vertical

alignment. A trunk twist then is simply the blue line rotating from

one side to the other of the red line.

Where both lines intersect is the Dan Jun (yellow dot), the central

balancing point about 3" below the navel. This is where our energy

resides and movement is initiated from.

When all these considerations are met and the correct amount of

power is added we are said to be in balance (Choong Shim). Movement

will then be fluid and effortless.

With the benefit of this illustration in hand, there are three

concepts to explore to help achieve fluid and powerful motion.

●

Offensive Hip

●

Defensive Hip

●

and

Pull rather than Push

Offensive Hip

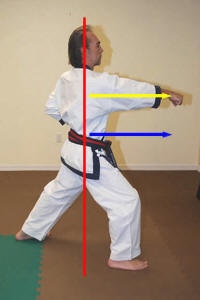

This is most often employed in Tang Soo Do attacks, although there are

some attacks where a defensive hip is used. For purposes of illustration

we will focus on the middle punch. Offensive Hip is characterized by

opening up of the hip, holding it back and then releasing it at the

moment of impact (the final step). You will note in the photos below

that the vertical alignment mentioned earlier is maintained. There is no

leaning forward with the upper body.

(Note: Because I am using snapshots rather than video, Figure

3 below would seem to be an actual step, however it is not. It is the

position your body would be in if we froze the video just before the

final hip rotation when the punch is released. In reality, the foot has

not even landed yet. The landing, hip rotation and punch all happen at

the same time as in Figure 4. The photo is meant to show that the punch

has not yet moved forward - a mistake commonly made by beginners where

their punch precedes the step.)

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1 |

Figure 2 |

Figure 3 |

Figure 4 |

Defensive Hip

With Defensive Hip you have a contraction, or closing in of the hips. It

is a defensive posture where we also present the smallest target to the

attacker. Figure 3 once again highlights the fact that the hip has not

yet turned and the blocking hand has not yet moved. As above, this all

happens in Figure 4.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1 |

Figure 2 |

Figure 3 |

Figure 4 |

Pull rather than

Push

This concept might be a bit abstract and difficult for some to grasp

because it is more mental than physical, and it relates to the Dan Jun

specifically.

When you push something you have its mass and weight in front of you. By

its very nature it literally and figuratively gets in your way. As a

result, students tend to overcompensate by applying more power than

necessary to drive their techniques home.

An analogy that my students are used to hearing from me is this. A

rear-wheel drive car driven in the snow has a greater tendency to

fishtail and lose control because it is pushing the mass in front of the

rear wheels, and the more power you give it, the worse it gets. With a

front-wheel drive car you are being pulled and because the mass is

behind you it simply follows where you steer. In addition, pushing is

more awkward than pulling. Try pushing something heavy across any

surface and then pull it and you'll see what I mean. It also takes less

energy to pull. You will also find that this concept is not limited to

just martial arts activities - a golfer pulls not pushes the club

through to the golf ball; a batter pulls the bat to the baseball, and a

fly fisherman pulls (whips) his line to his target spot in the stream).

To implement this type of motion, whether you're in Offensive or

Defensive Hip, think of a string tied to your Dan Jun point and that

there is an outside force (not your own) that is pulling you forward.

Imagine now that forceful pull suddenly stopping (as in hitting the

brakes on your car). What happens next is "inertia" - everything wants

to keep moving forward until it comes to a snapping halt. This is what

happens to your punch or block. When done correctly, it goes by itself.

You "become" the punch or block. The greater the pull the more power in

the technique at the end. Of course you must again remember that what

prevents your whole body from falling forward is keeping it aligned with

the vertical axis.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1 |

Figure 2 |

Figure 3 |

Figure 4 |

As a further aid in

your practice, try this simple exercise. First walk across the room as

you normally would and try to sense where your propulsion is coming

from. Next, switch your awareness and visualize a string tied to your

Dan Jun which is being pulled by someone else, and with your back

straight, just go with it. It will probably be very awkward at first but

with practice you will begin to feel as if you're gliding along as

opposed to being pushed across the floor.

Like everything else we do in our training, the benefits to

understanding and putting these concepts to use spill over (in a

positive way) to other tasks we perform in our daily lives. These may even

change how you move entirely.

I hope you find this useful in your continued studies. |