|

About The Author

"I have been studying Soo Bahk Do Moo Duk Kwan since January 2001. Currently, I train in Cambridge, MA but I am still connected to my original instructor, Master Eui-Sun Choi, whom I fell upon unwittingly at fourteen. I see him as often as I can throughout the year.

"In 2006, I moved to Boston to finish my degree. I carried on my training with Boston Classical Soo Bahk Do, where I have been teaching and training since."

"I wrote this two years ago (and amended it a few times since) in the hopes of getting it in the paper, no such luck. This is the massively abbreviated story of his fascinating life, which he was so kind to share with me for the article."

Cultivating Spirit

Master Eui-Sun Choi sits, back straight, on the edge of a folding chair in the office of the Korean Martial Arts Academy in New Milford, Connecticut. His hand rests on the handle of a pot of boiling water, which sits atop a kerosene heater. He drops a few sticks of cinnamon into the pot.

"I think is boring, my life," he says. He speaks carefully and with a deep, guttural Korean accent. English is his third language. "I am here. Only present matters."

When he leans back in his chair, his heels don't touch the floor. Dressed in his white, pressed uniform he is intimidating in spite of his small stature. He stands at a mere five feet with his belt tied snug around a tiny waist. Time doesn't concern him, nor the long silences he leaves between thoughts. Choi (pronounced "chey"), 45, a former Buddhist monk, French citizen, and martial artist fully recovered from a broken back, is far from ordinary.

|

|

|

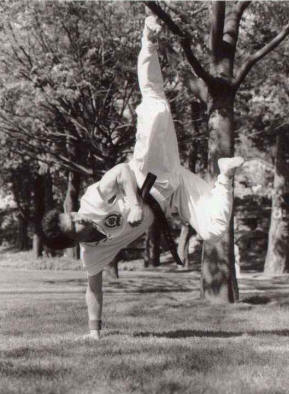

Master Eui-Sun Choi - Photo courtesy of Ms. Elodie Mollet |

|

Choi is a master of the little known Korean martial arts style, Soo Bahk Do and the owner of two Connecticut studios. In February of 2009, the Grandmaster awarded Choi with his 7th Dan rank, making Choi one of the highest-ranking members in the organization. Well deserved, because in addition to over thirty-five years of training, Choi endured an eight day promotional test in the mountains of South Korea to be considered as a qualified candidate. The test is unusual to Soo Bahk Do and requires practitioners to endure a rigorous training program as well as work together on creative projects to further the organization's mission and expand its philosophical grounds.

Just two years after the opening of his Danbury location, Han Dol Martial Arts, Choi's students new and old gathered to celebrate his achievement. Choi, who opened his New Milford school in 1999, runs both schools full time for all ages with the help of Master Frank Tsai and his senior students, many of whom have been with him for nearly ten years. Students are drawn to Choi because of his traditional teaching, rigorous training, and charisma - but there is a depth to Choi that goes beyond a good workout.

Born in Seoul, South Korea, Choi was raised in a Confucian family where it was typical for children to learn traditional literature, games, and arts from a young age. At five, Choi was enrolled in Soo Bahk Do, then the most well known martial art in Korea. For his first six months, he learned only the most basic techniques and cleaned the studio floors.

"At the time was very hard, the training. Sometimes I asking by myself to stop because it is so hard, but my parents guide me to continue," he says.

By the time Choi was ten, he had received his Cho Dan (1st degree black belt). His instructor, Lee Chang-Yong, left to train the king's guard in Malaysia and introduced him to the Grandmaster, whose studio he trained at from then on.

"After Cho Dan I realize there is a lot of difference between Soo Bahk Do and the other martial arts because it is so hard to be a Cho Dan in Soo Bahk Do and I was proud what I had through hard training," says Choi.

Pride and hard work are clear themes for Choi, who even at rest appears deliberate and collected. His studio, which is carefully decorated with carvings, calligraphy, and rice-paper windows he made himself, is like a slice of Korean culture, undisturbed, like Choi, by its American setting.

Student John Sotherland, 19, says Choi's attention to detail has taught him nearly as much as his grueling training. "He made me realize that all of the little things are component of who we are," he says. "I value things I would have otherwise overlooked."

By eighteen, Choi received his master rank and enjoyed training in Soo Bahk Do but hadn't considered it as a life path until after he entered the military at twenty.

"That time my life totally change," he says and laughs at the understatement.

Military training in South Korea is compulsory, but due to Choi's participation in protests against the military dictatorship, he was arrested and forced to leave his university early. In lieu of going to prison, Choi was trained as a low altitude paratrooper. Choi's life took its major turn when a senior officer beat Choi into a coma and broke his back. He was not expected to live, but to the doctor's surprise, Choi woke up. Though he was paralyzed and unable to walk, Choi diligently practiced walking and during the night reviewed his Soo Bahk Do forms in his mind.

|

|

|

Photo courtesy

of |

"One day I feel my spine," Choi says. "The muscle has the feeling and I start to stand. I was so surprised by myself. I was so happiness - I am alive."

Although the doctor said it was a miracle that Choi could walk, his body would never be the same. Persistent, Choi began stretching and practicing Soo Bahk Do. "[There was] a lot of pain. Sometimes I didn't have the feeling in my right leg or arm. But I was fight, and I get up."

Choi's belief that discipline is a source of spiritual freedom not only ensured his survival but profoundly influences his teaching.

"In Western countries, we like thinking we are free person," writes Elodie Mollet, 32, a former student, in an email from Paris, France. "When we practice physical activities, we cannot easily imagine it as a way to educate yourself. Being Master Choi's student to me means: you always have something to learn, every moment of your life."

Choi's days as a paratrooper were over, so he finished out his military duty as a Tae Kwon Do instructor and returned to society at twenty-four as an instructor at the U.S. military base and headmaster at Soo Bahk Do headquarters in Seoul.

Unable to return to school, Choi passed time aimlessly until one day he was approached by a Buddhist monk, who asked him to be his disciple. At first, Choi refused, but the monk insisted, challenging Choi to block his kick.

"He was so fast I couldn't even move my hand," says Choi.

Choi lived with the monk at the monastery doing nothing but hard training for one year. Then, in 1989 Choi made a sudden, one-way departure for Paris, France.

In France, Choi lived with the homeless until he discovered a Karate school where he lived and taught until he established his own independent school. He stayed in France for ten years as head of the European Soo Bahk Do Federation and moved to the States in January of 1999, where he opened his first studio in Connecticut that November.

Choi has had an enduring impact on his students in France and the United States. Mollet, a student who trained with Choi in France still practices and teaches Soo Bahk Do and remains loyal to him. "I recently heard someone saying Master Choi teaches not only technical and physical exercises but also a way of life," she e-mails. "I agree with that. As his student you cannot feel it immediately. You need time to realize it."

"[Choi is] invested in his students," says Sotherland. "He's very quiet, but there's more to his quietude than not saying anything. He gives real opportunities (for his students) to grow just by showing us how to do it. He teaches by example."

"I think I'm mostly loyal to the others," Choi says. Many of his most dedicated students stay with him for many years and he is touched by his students in France and Korea who don't forget him. "They have no reason to be loyal to me."

"Whenever Master Choi talks to anybody he doesn't ever say, 'my student'" says Master Dae-Kyu Jang, longtime friend, of Santa Barbara, CA. "The first time he introduced me to his students he said this is my daughter, my son. Everyone was like, 'WHAT? Is Master Choi married? What does he mean?' They think he's making a joke but he is really serious. That's how he sees his students - as his children. He means that very sincerely. I think this shows a very warm spirit."

With two modest Connecticut schools, Choi strives for success through sharing discipline. "Discipline means to become human being," he says. "Uncontrolled person has no wisdom. The person who has no wisdom doesn't have concentration. The person who doesn't have concentration has no peace. That person has no happiness. If somebody uses Soo Bahk Do is become very violent, but when you make control is become beauty."

"He's a model," says Jang. "What he says his spirit exactly matches. He just wants to share an art with feeling. It's obvious."

As soon as Choi steps out of the studio he breaks his brooding demeanor. With a big smile on his face he razzes the children coming in for class, holding a small boy over his head with one arm and talking cordially with parents. To Choi, Soo Bahk Do is a way to find happiness, and it is this sentiment that seems to cheer others.

"Well is a lot of study [my life], eh?" says Choi. "Boring, eh?"